-

5. A Slice of Paradic/se

A Victorian cookbook, charmingly titled Little Dinners: How to Serve Them with Elegance and Economy (1877), by Mary Hooper, claims to show ‘How the best use can be made of cheap material, and helps to revive what threatens to become a lost art in the home.’ Indeed, 150 years ago there were grumblings about the dying art of economy and self-sufficiency. Writers were moaning about this in earlier times, and continue to do so today. History does tend to repeat itself.

Nevertheless, perhaps there is in fact a market for books that stress economy today, when we are more aware than we have been for many generations, on the importance of frugality, the need for sustainable choices, the value in wasting less to have more.

All this serves as a talking point for recipe #5 in The Cookbook. What happened to 3-4, I hear you cry? Good question. That page is missing. Perhaps the original writer made an error she didn’t want to preserve, or perhaps it fell out years ago and found its way to the bin rather than back into the collection. All we know of recipe #4, from the part of it that slipped onto page 5, is that it was another boiled pudding, served with custard. My kind of pudding.

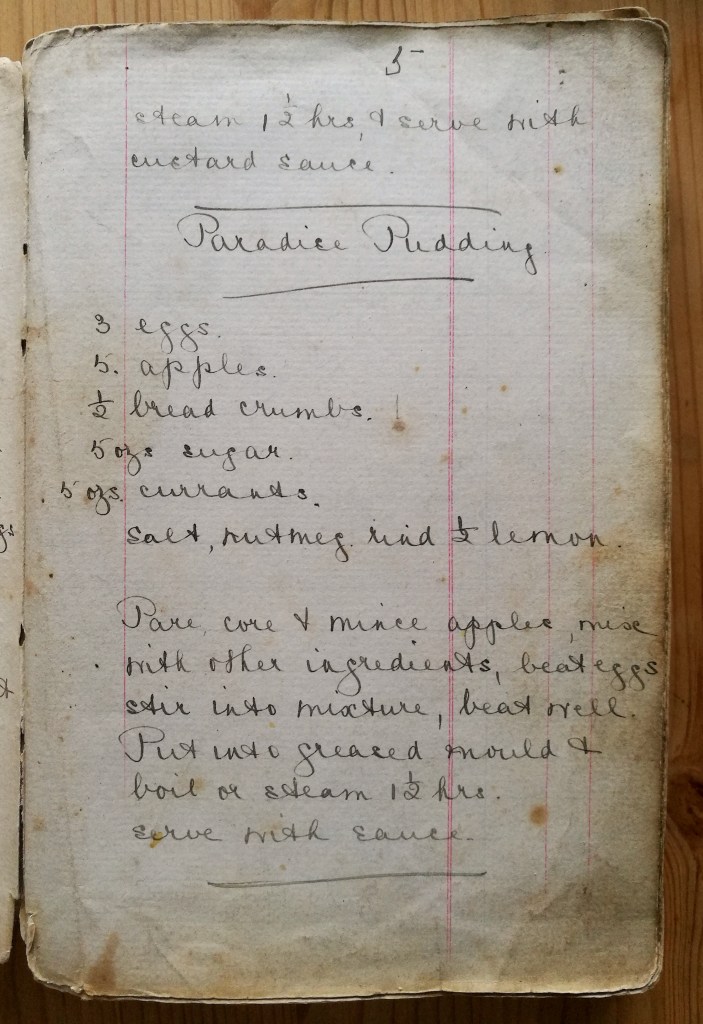

Recipe #5 is for Paradise Pudding. I did some research to see if I could find other examples of this recipe, and to see how far back I could take its existence. This particular Paradise Pudding is not to be confused with a dessert of the same name originating in the 1920s that makes unholy combination of marshmallows, maraschino cherries, whipped cream and Jell-O. This Paradise Pudding has so much in common with Pudding a la Rachel (recipe 1) that I’m frankly surprised to see both in quick succession in the same family cookbook. Why would you want to have both? It’s so similar, in fact, that I include it here for the aim of completism of this project, but I have decided not to actually recreate it.

Paradise Pudding

3 eggs

5 apples

1/2(lb) bread crumbs

5oz sugar

5oz currants

salt, nutmeg and 1/2 lemon

Pare, core & mince apples, mix with other ingredients, beat eggs, stir into mixture, beat well. Put into greased mould & boil or steam 1/12 hrs. Serve with sauce.

The main difference with this pudding is that it does not use suet, but does include sugar. Perhaps the point of having both is to ensure you’ve got options, depending on the ingredients on hand in the larder? The Little Dinners version runs as follows: Six ounces of bread crumbs, six ounces of sugar, six ounces of currants, six apples grated, six ounces of butter beaten to a cream, six eggs, a little lemon peel chopped fine, and a small quantity of nutmeg. Boil in a shape three hours. Serve with wine sauce.

I do like ‘Boil in a shape.’ This version includes a hefty addition of butter to the pudding batter. Little Dinners however might have been a bit cheeky in sourcing this recipe. It appears almost identically in The Illustrated London Almanack for 1851:

Potentially the most widely referenced version of the recipe, one which, like the one in our Cookbook, contains no fats at all except a small amount of butter in the mould, occurs in Isabella Beeton’s The Book of Household Management where it has graced the puddings section since its first edition in 1861. The text of 1896 version:

Paradise Pudding Ingredients. — 3 eggs, 3 apples, ¼ lb. breadcrumbs, 3 oz. sugar, 3 oz. currants, salt and grated nutmeg to taste, the rind of ½ lemon, ½ wineglassful brandy.

Mode. — Pare, core, and mince the apples into small pieces, and mix them with the other dry ingredients; beat up the eggs, moisten the mixture with these, and beat well; stir in the brandy, and put the pudding into a buttered mold; tie it down with a cloth, boil for 1½ hour (sic), and serve with sweet sauce.

One source, pictured here, suggests that this recipe is even older, though no definitive date can be attached to the manuscript available online under the title An Anonymous Collection of Culinary and Medical Reciepts. Other than for its poetry, this last version of the recipe is valuable as well for its clear identification of where the name of this pudding originates – the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden, or Paradise. “Take of the same fruit which Eve once did taste, Well pared + well clipped, half a dozen at least.” Towards the end of the text, in a moment of reader reassurance, “Adam tasted this Pudding twas wonderous.”

There are other versions of this recipe available for comparison, but you get the general idea. The ratio of ingredients varies slightly, with more apples or fewer, fats or no fats, more or less sugar, booze or no booze Here is another recipe for which you need only the most basic and widely-available ingredients, some lemon to tart it up and potentially a bit of booze in the pudding or in the sauce to give it a warming and digestive flair.

-

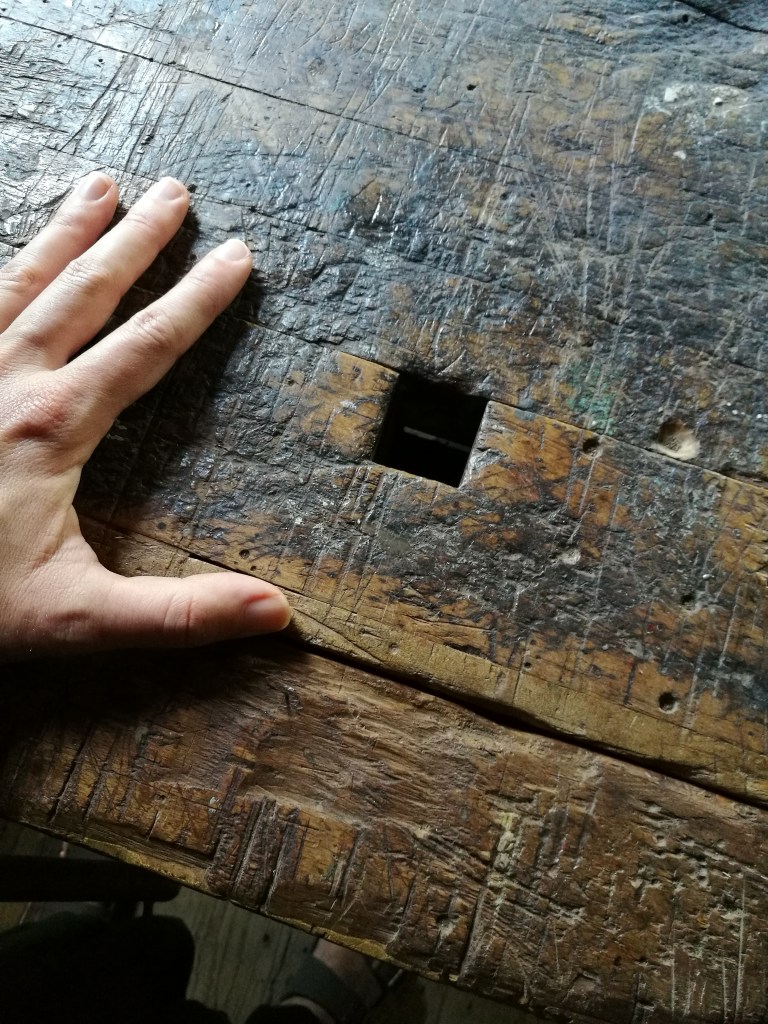

The Hazel Frame Pack

Of all the ‘historical’ goods I have made over the years, the object I am most proud of must be the hazel frame pack that I started making in February of this year and didn’t complete until June, though ‘complete’ is a bit of a misnomer as I have tweaked and fiddled with it regularly since.

I recall its birth well. Train disruption had put an end to my hopes to visit West Stow Anglo Saxon Village that day, and so I went foraging instead. I must have been in a particularly historical frame of mind, though that usually describes me. It was a beautiful day – one of those sunny and warm late winter days that make you hopeful for spring, when the earliest blossom is just starting to peek.

There is a place near me that used to be a dump, for many, many years until the mid-90s when nature and a team of invested locals decided that it needed to be reclaimed. Now, rabbits burrow into embankments stuffed with Victorian glass. They carve out treasures with every new tunnel. Above ground, species variety is improving. The soil is thin and a bit starved still, but there are beautiful open meadows crisscrossed by well-established hedges and a few thickets of native hardwoods. I come here often, in all seasons, willing to learn what the land has to teach.

I didn’t expect to start work on a frame pack that day, though I’d been researching Ötzi the Iceman and his fabulous collection of possessions just the previous day, so the idea didn’t come out of nowhere. What happened was, I saw the hazel: Warm brown and with an unmistakable sheen, it was peeking between field maples and hawthorn. I had an apple in my bag. I traded it for a long, straight sucker stem that was deeply embedded, snaggling many other canes in their race to the sun. A bit of thinning would be good for the tree, so I took out my pruning saw. A few paces away, some windfall cherry caught my eye. Ötzi’s pack had thin larch-wood boards keyed into slots at the side of the bent hazel pole that made up the larger part of his carry frame. Mine would be a simpler affair, as I intended to lash the crosspiece to the frame.

I took these, and a few other bits and pieces home, ready for an afternoon of making. The hazel pole needed stripping of its bark – an easy task in the early spring, and soaking in hot water to encourage it to bend. The fibres of the young wood did want to split a little, and the resulting frame is flattened across the top as a result of some of the outer layers of cambium peeling away, but the frame is very strong regardless.

After an hour or so of soaking in very hot water, I used string to pull the two ends together until the sides were parallel. I used my knee and good old-fashioned eyeballing to encourage the bend across the middle to be even. I figured the more I could do that would keep tools simple and the majority of the work in my own hands, the closer I would get to the spiritual truth of the project.

While the frame dried, I got to reading. The frame pack didn’t survive complete and it is surmised that it may have included a net bag to carry his possessions in, including the famous birchbark containers used to carry charcoal and other goods. The pack may instead have had a hide bag, but so much of what he had was made beautifully out of handmade twine, I liked the idea of a net bag.

This is where I feel the need to stress that I was not trying to recreate Ötzi’s pack. I wanted to be inspired by it, and use my traditional skills to make the components of a pack that wouldn’t be out of place in the prehistoric world, or indeed in the context of the many world cultures that still see value in being able to use local materials and traditional skills to make similar carry systems today. I have been an avid backpacker, long-distance walker and wild-camper for many years. There were things about Ötzi’s pack that struck me right away as excellent design, regardless of time period. If you are walking high in the mountains for long stretches over uneven terrain, as Ötzi was, you want something small, lightweight and practical. Ötzi’s pack was large enough just to carry the essentials, and all his possessions were, to use a modern outdoor pursuits term, ‘ultralight’. He may have been (unsuccessfully) running for his life, so it makes sense that he carried so little, that he left precious, heavy, and breakable pottery at home, etc.

A net bag made sense in this case – super light, flexible, and quick to dry. Plus you can see where everything is. I had a good hank of partly-processed flax fibre in my stash. Knowing that it would take a large amount of twine to loop a bag big enough to make sense on this frame, I got to work. I didn’t keep track, but I figure that it must have been about a hundred hours of work to make the twine for the various string elements of the pack. It might be more.

There are four distinct prehistoric fibre crafts in use on this pack, besides the twining itself: Sprang, looping (the earliest ancestor of nalbinding, or needlebinding), looping around a core, and braiding.

I used another snowshoe-like frame to act as a sprang loom on which the two shoulder straps were made. I took time to think about how I wanted to do the straps (leather being obvious, but I was determined to make all element of this pack vegetal), and landed on sprang because it, well, springs. The web will stretch to be broader over the shoulder to add comfort, while narrowing under the arm for ease of motion. The straps are a combination of hand-twined flax and lime bast for added strength. Sprang was also used to make a net that would fill the square space in the middle of the pack frame, to stop the bag and whatever else was tied to the frame from falling through against my back while carrying.

The bag itself is a combination of looping and looping around a core – used in the base to provide extra rigidity and strength, and to close up holes so that no small articles could accidentally slip out. The pace of looping, done with a handmade antler needle, is slow enough to let you think through what you want to accomplish. As such, I was able to tighten up the weave towards the bottom of the bag where the ends of tools, etc. might want to poke through. I kept it looser at the top to help with flexibility. Many (many) a pleasant afternoon and evening hour was spent quietly making twine and looping. I liked to make about 12 feet of twine at a time to add to the bag as it grew, measuring it against the frame until it sat comfortably between the top crossbar and the bottom one. The final row of looping incorporated a rod that would be fixed to the top of the hazel frame (loose enough for easy removal of the bag from the frame). A simple length of twine became the closing tie.

At this point, all that was left was to put the thing together. Plenty of extra twine was needed to tie the various frame pieces in place, as well as the other flax elements, such as by whipping around the entire top cross bar to fix the straps and the sprang back net in place. Still, this all had to be hand made by me.

After the first carry, I made the main adjustments, as I like to imagine Ötzi would have done at a less fraught time in his life, when he (or someone in his community) first made that remarkable pack that survived in a recognisable form for 5000 years. I strengthened the shoulder straps by applying a braided edge down all sides, and made the bottom parts of the straps more substantial, for ease of sliding the pack on and off. I also fixed the net bag in place a little better to stop it flopping around with a load in. I also shortened the ‘feet’ of the frame by an inch or so, to stop getting poked in the hips while I walked.

Since then, it has required just minor adjustment, tightening a lashing here and there, and keeping it out of the damp. I’ve treated the wood with cedar oil to help keep it mildew-free.

This summer I made a birch bark container, again using hand-plied twine as well as bark from dead fall birch near home. It’s a remarkable material to work with – so like leather in its pliability and strength, so long as you respect the grain of the fibre. It makes a perfect insert into the mesh bag in which to carry your worldly possessions. I’ll do another post on this process, if you like.

Currently, I use the frame pack to hold everything that I’ve made under similar principles – a lipwork rush basket, for example, containing an entirely handmade and organic sewing kit, bits of flint, a handspun and handwoven shawl, shells full of pine pitch glue, dried birch polypore and chaga mushroom, again in a nod to Ötzi and his medicinal kit. It’s an easy item to fling over a shoulder to take to teaching venues, but keeping it all together has another purpose. Should disaster strike, it’s an easy way to make sure these precious things – representing hundreds of hours of work, rather than richness of materials – can quickly and easily be saved from destruction. Yet, it gives me a moment of quiet reflection when I remember that under most circumstances, these precious items wouldn’t last more than a year or two if left out to rot. There would be no trace of the materials or the skills used to create so many things of daily practical use. This is very much what draws me to this kind of skill and this kind of material – knowing that 98% of the material culture of our ancestors leaves no trace in the archaeological record.

Can we learn something from this? About self-reliance? About what constitutes value? About living resourcefully, locally, and sustainably? I think so. How about you? Leave your thoughts in the comments. All are welcome.

ancient craft, bronzeage, bushcraft, bushcraft skills, chalcolithic, cordage, experimental archaeology, flax, handmade, handmade tools, handweaving, heathen, historical reproduction, iron age, limebast, linen, living history, looping, naalbinding, nalbinding, neolithic, otzi, otzipack, prehistoric, prehistoric craft, primitive technology, sprang, twining

ancient craft, bronzeage, bushcraft, bushcraft skills, chalcolithic, cordage, experimental archaeology, flax, handmade, handmade tools, handweaving, heathen, historical reproduction, iron age, limebast, linen, living history, looping, naalbinding, nalbinding, neolithic, otzi, otzipack, prehistoric, prehistoric craft, primitive technology, sprang, twining -

2. Fig Pudding: Touching history

I’ll do my best to write about fig pudding without mentioning Christmas.

Whoops.

In truth, this recipe doesn’t much resemble a holiday classic: no fruit other than the figs, no spice and no alcohol. The recipe given as number two in the collection has much more in common with very old recipes for fig pudding, which tend to be simpler in terms of ingredients and instruction. One of the earliest boiled ‘fygey’ pudding recipes comes from that famous 14th century cookery book, The Forme of Cury. Dried figs, being lightweight and fairly bombproof, were widely available in Britain in the medieval period, which explains why they, as with dates and raisins, appear again and again in ancient recipes as well as their modern equivalents in the canon of ‘Traditional’ British sweet dishes. They were exotic and luxurious while also being accessible, price wise, for most. The medieval recipe by today’s standards ticks many dietary boxes: vegan-ish and gluten-free, but characteristically lacks most of what we would expect in the way of instruction.

FYGEY. XX.IIII. IX.

Take Almaundes blanched, grynde hem and drawe hem up with water and wyne: quarter fygur hole raisouns. cast þerto powdour gyngur and hony clarified. seeþ it wel & salt it, and serue forth. —The Forme of Cury recipe 118Take blanched (peeled by boiling) almonds, grind them and mix with water and wine, quartered figs, whole raisins. Add to this powdered ginger and clarified honey. Boil it well and salt it, and serve it up.

This sweet dish isn’t to be confused with ‘Fygey’ from later in the same volume: a fish and onion stew. Isn’t English wonderful?

Even this very early recipe, which bears more than a passing resemblance to dishes that would have been familiar in the ancient Classical world, calls for spice and wine, which our late Victorian recipe does not.

These omissions make me think that the recipe included in this book, like the previous one, Pudding a la Rachel, was viewed as simple, everyday fare as opposed to the kind of ‘speckled cannon-ball…blazing in half a quartern of ignited brandy’ that would have been special enough to flush Mrs Cratchits’ cheeks.

This recipe comes with one or two mysteries. The milk, for example, in a slightly more thready pen stroke, comes without measurement attached, but next to ‘eggs’. This makes me think that the liquid volume of 2 eggs, on trying the recipe, left the mixture too dry, so milk was added until the right consistency was achieved. This accounts for no measurements – the point is to remind the maker that milk may or may not be needed, and it should be used by gut feeling. The second mystery is the mention of ‘moist sugar’ – which could be white sugar which does not come in hard, dry lumps, or it may refer to brown sugar. I have used brown sugar in making mine, as it would lend some very welcome warmth of flavour to the finished product.

It’s a reminder that for many, practice and experience gave cooks a ‘feel’ for things, and that cooking was an instinctual art, rather than a science. Anyone who has spent any time reading old cookbooks will know how minimal, how barely suggestive, many recipes are. A recipe for chicken pie might be rendered as briefly as ‘Make a pie. Fill it with chicken and serve with sauce.’

While recipe one made this collection feel as if it was in conversation with recent food fashions, this recipe is full of echoes from the distant past.

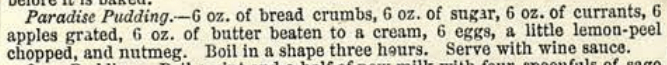

Fig Pudding

1 lb (454g) figs

½ lb (227g) suet

¾ lb (340g) bread crumbs

¼ lb (113g) flour

2 eggs (milk)

¼ lb (113g) moist sugar

Chop the figs small, & suet, grate bread, mix all well together, add eggs well beaten, butter basin, press down closely. Tie over with cloth & boil 3 hours. Serve with sweet sauce.

A quarter recipe, for convenience

113g figs (7 approx.)

57g suet

85g bread crumbs

28g flour

1 egg (milk)

28g moist (brown) sugar

Follow the simple instructions above. I used one whole egg and no milk and achieved a perfect ‘press-able’ consistency. The moistness of your breadcrumbs may yield different results, so use your judgement. I buttered a small pudding basin, pressed in the raw pudding, covered it with buttered baking paper then used a circle of damp 100% white cotton (from an old bedsheet) and a piece of cotton string over the lip of the bowl. Into a saucepan I put the basin, covered with a saucer, added boiling water about halfway up the sides of the basin, and lidded the pot. Brought it to a simmer and steamed the pudding for 1 hour.

Cook’s notes

This pudding doesn’t ‘sing’ in the copper as Mrs Cratchit’s did. Instead, it tap-dances. What’s helpful about it is that you can hear if the water is getting low without having to peek.

Provided you enjoy very simple flavours, this pudding is a homely, comforting treat (I have had mine with a good dollop of hot custard). The toasted breadcrumbs provide just as much flavour as the figs and the brown sugar, so it’s definitely bread-pudding in profile. Served warm, the pudding is dense and chewy, not overly moist. I might have needed to add milk after all, or possibly reduce the cooking time. In any case, it’s perfectly edible.

Does it want more flavour? I’d be tempted to add a pinch of salt, possibly some nutmeg, and no doubt our original recipe writer would have felt free to as well. A recipe is just a suggestion, after all.

-

1. Pudding à la Rachel: or how to cash in on the power of celebrity

The oldest reference to Pudding à la Rachel I have been able to find is an 1855 reference in the journal The Musical World, the dish reportedly being offered in a Broadway dining house that year for the first time. It was named after a French actress, Elizabeth Félix, known professionally as Mademoiselle Rachel, following a tour that took her to New York in 1855. Such was her fame that her name started cropping up everywhere in New York that year. You could have your hair done à la Rachel in the first, but definitely not the last, moment of celebrity-driven fashion associated with that name.

Eight years after Mlle Rachel’s death from tuberculosis, the wonderfully titled 1865 cookbook, How to Cook Apples; Shown in A Hundred Different Ways of Dressing That Fruit contains a recipe for Pudding à la Rachel. The recipe differs slightly – the apples are shredded rather than chopped, ‘grocer’s’ currants rather than sultanas are listed, as is the rind and juice of both lemons. The cooking time is reduced to 3 hours and the sauce is specified as a ‘wine sauce’.

A further mention of Pudding à la Rachel is found in the 13 February 1891 copy of The New Zealand Mail as part of a special on apple recipes, with wording very similar to that in the instructions transcribed below, though 4 eggs is suggested rather than 3, and a whole teaspoon of cinnamon or nutmeg but not both. Here, a wine sauce is also recommended. Clearly this recipe had found a quiet place in gastronomy as a handy standby to use up apples.

In fact, despite the glamour suggested by a treat developed on Broadway to honour the visit of a French stage celebrity, the ingredients of this boiled pud are what you might find in the larder of any household of the period, or indeed at the time this recipe book was begun (in or prior to 1907). By the 1850s, around 300 million oranges and lemons were imported to England yearly, according to Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor. Domestic production would have made lemons even cheaper and more widely available in the US.

One can view this dish as something of a standby, simple everyday fare, requiring no special or expensive ingredients. Nevertheless, for one or perhaps all the above reasons, this recipe was enough of a favourite to be given the distinction of being the first listed in this collection, in the hand of the first contributor.

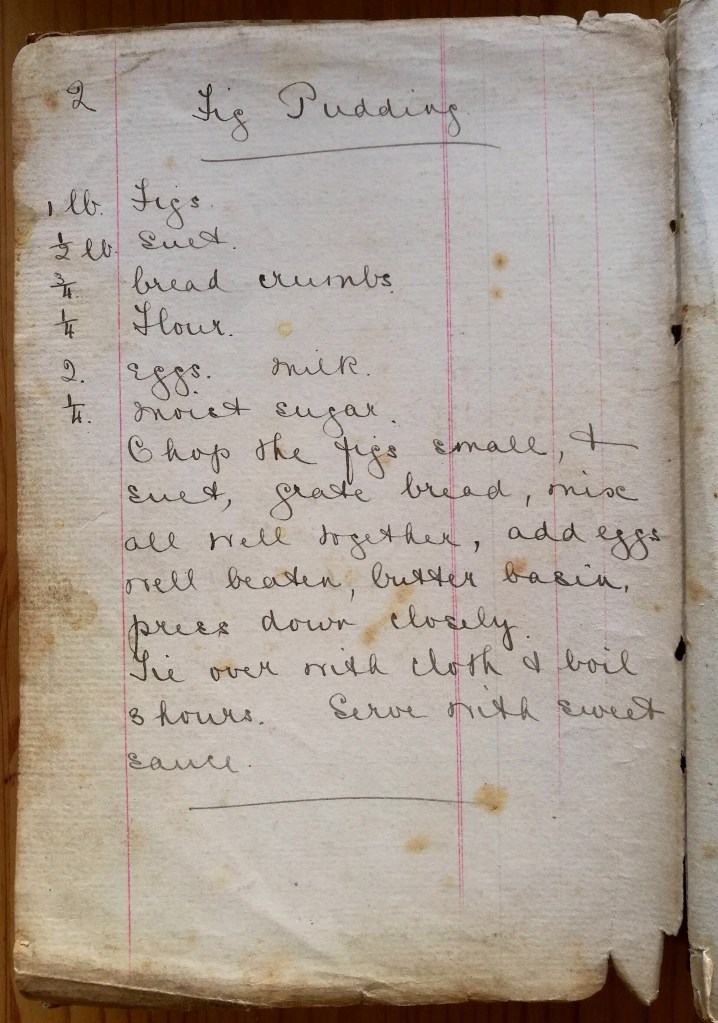

Original Recipe (modern weights and measures given)

1 lb (454g) bread crumbs

1 lb (454g) apples (chopped or grated)

½ (227g) suet

¾ (340g) sultanas

½ teaspoonful nutmeg

Rind (zest) 1 lemon, juice of 2 lemons

3 eggs well beaten

Mix all together – put into well buttered mould, place buttered paper on top, & boil 4 hours – Care must be taken that water does not come within 3 inches of top of mould, & saucepan to be well covered. Serve with sauce.

A Victorian wine sauce recipe

140ml of water

30g of caster sugar

A squeeze of lemon juice

2 tablespoons of apricot jam

A glass of sherry or claret

Combine ingredients in a small saucepan until combined. Spoon over the pudding at table.

Cook’s notes

I made half a recipe which was enough for an 8” diameter pudding basin. I used currants, because that’s what I had (in a nod to thrift), a good half teaspoon of nutmeg, the juice and rind of one lemon, half a pound of white bread crumbs, half a pound of grated apples, a quarter pound of shredded beef suet (Atora) and two medium size eggs. The mixture was not too wet and pressed well into the buttered basin. It was easy to seal the surface with a piece of buttered baking paper pressed to the sides of the basin a little. I steamed the pudding, covered, for 2 3/4 hours but could have gone for less.

It felt very odd not having sugar or salt in the mix. If it weren’t for the suet I’d have suggested this was a very healthy recipe. The sauce, however, is not essential to the enjoyment of this pudding. By itself the cake is moist and very flavourful, fresh with lemons and apples and deeply sweet with the dried fruit. I don’t miss the extra sweetness or the salt. If you are looking for a lighter, easier alternative to a Christmas pudding, this may well be it. The sauce is a real treat on top however, and pairs beautifully. I used sweet cream sherry in mine, and an extra one in a glass alongside.

-

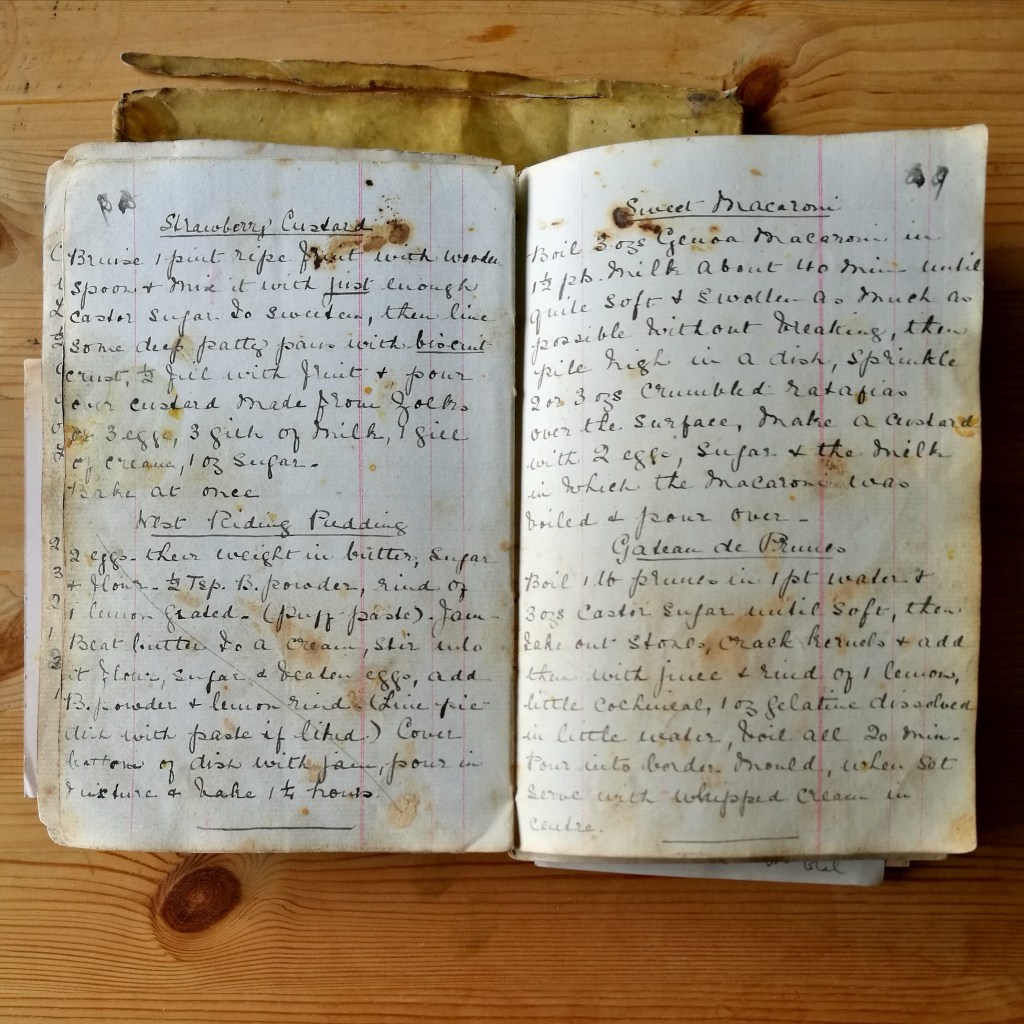

A family book of recipes ~1900s-1970s

A professional acquaintance, on clearing her house a few years ago, gave me a book of recipes. It had been compiled by women who meant a great deal to her, a pair of sisters and their mother, teachers and school mistresses who moved from Sussex to Oxfordshire in the first half of the 20th Century.

It was my friend’s plain instruction to ‘Keep this book, or burn it.’ The volume isn’t large, but I felt its weight as it came into my hands.

The collection is entirely hand written, though in later pages. numerous clippings and leaflets have been stuffed, as well as short items of personal correspondence. The earliest dated recipe is from 1907, though that entry is well into the book. The earlier recipes likely come from earlier that year or even from previous years.

This was an interesting time in British food history – perhaps what is most striking is how little the recipes change, despite covering both the First and Second World Wars, and their accompanying rationing and other limitations. These women were not wealthy, and their ingredients are both modest and repetitive, but dream of a touch of elegance.

There will be a section of this website devoted to photographing and transcribing these recipes, trying them myself for further notes.

If anyone comes across other interesting sources for the history of some of these recipes – and there are some great names in the collection, please leave your comments below. Thank you.

-

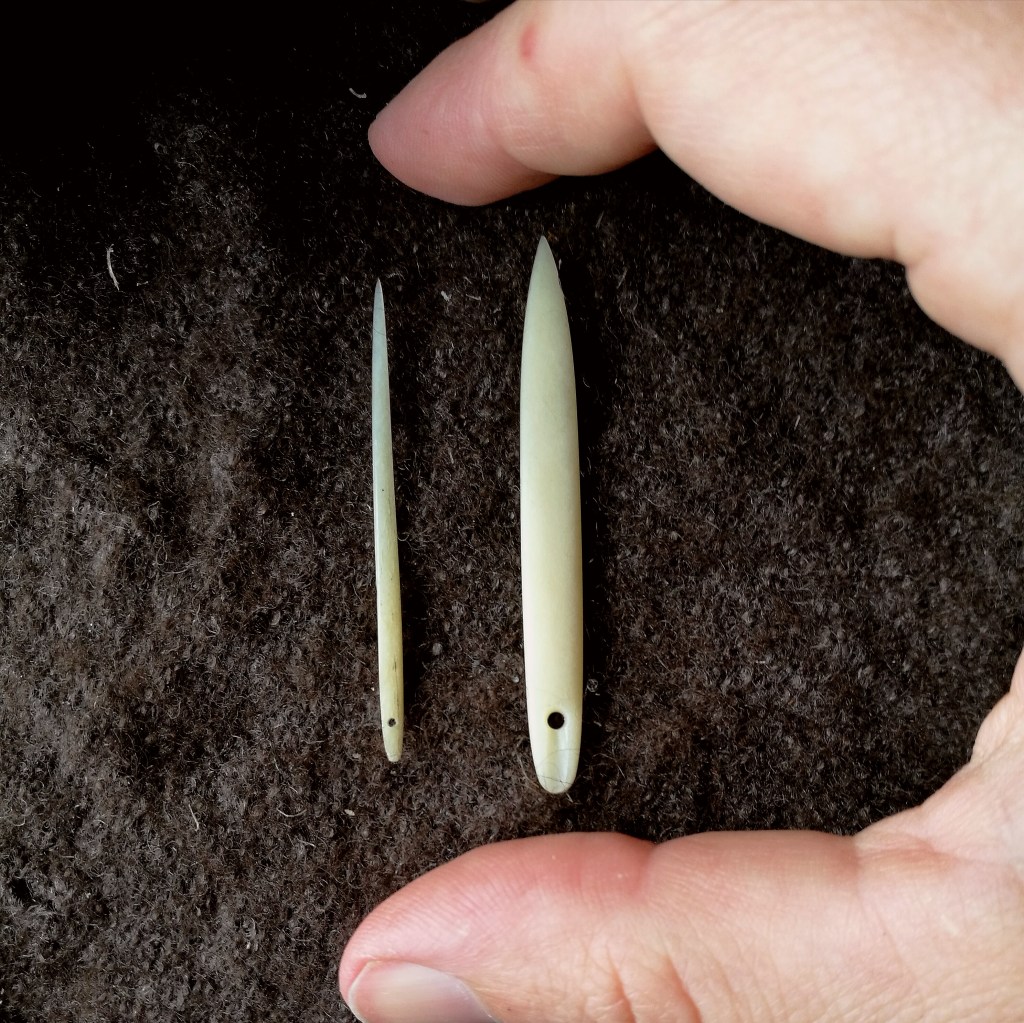

Bone needles: Waste Not Want Not

I haven’t used a steel needle in years. The reason for this is that from the very first time I made a bone needle, I fell in love with this ancient and versatile material. Bone needles are rare among archaeological finds; being an organic material and by nature quite delicate, they will simply disappear into the soil under most circumstances.

The number that do survive, when the conditions are perfect, suggest that many more went into the ground than are now able to be recovered from it. Eyed needles are among the clearest indicators where (and when) sewing was a craft carried out by our ancestors, among the earliest being, potentially, a fragment of one recovered from a cave in South Africa. Astonishingly, this object has been dated to around 61,000 years ago. Large-eyed needles could be used for netting, basket looping, simple sewing, and other applications. By the Neolithic, people started to sew cloth as well as skins together to make clothing and other useful objects.

Horn, antler, and bone – including bird bone – is fine enough to create a tool that is smooth and slender so as not to punch great holes into the material being sewn, but flexible enough so as not to be brittle.

I like that a bone needle will push between the warp and weft of fabric, rather than punching through it, so the weave can close up around the sewing thread and sustain less damage than can be done with a standard modern steel needle. It has a lovely texture in the hand, with good grip, and will improve with use – every time it passes through your sewing material, it will get smoother and smoother.

The instructions below are to make a bone sewing needle using a few modern hand tools. Historical equivalents are possible. I’ve had great success with soaked antler, using flint blades and sandstone grinding stones. For this needle I’ve suggested lamb bone as it is very easy to come by. A single lamb dinner (shanks or leg) will give you enough raw material to make many needles and other trinkets. Part of the beauty of making your own tools like this is the opportunity to show respect for the animal by using more of it – nothing need go to waste.

How to make a bone needle

Materials and tools

- Lamb bone (such as from a leg or shank)

- Face mask

- Pencil

- Fine saw

- Pliers (optional)

- Vise (optional)

- Dremmel drill, hand drill, gimlet or awl

- Sandpaper in 80, 120, 240, 400, 600

- Strop or smooth leather strap (such as an old belt)

Instructions

- Boil the cleaned bone until any remaining material, such as marrow and cartilage, comes loose and you can wipe it clean. A good soak with some dish detergent will help degrease it. If the bone is whole, with no avenue of escape for marrow, saw off one joint end of the bone to aid with the cleaning process.

- Allow the bone to dry thoroughly, in the sun if possible to aid with bleaching.

- Work outside or near an open window and wear a mask. Bone dust is dangerous to inhale. Don’t skimp on this safety measure.

- Decide how large a needle you wish to make and start by creating a blank larger than you intend the finished needle to be – you can’t add bone later. Select a portion of the bone which is relatively straight, smooth, and free of butchery marks or artery holes (the nutrient foramen) and pencil in your blank.

- Brace bone in a vise if desired, and use saw to cut across and along bone to free the blank. It may be possible to score deep grooves in the bone and split it out using a pair of pliers, but be aware that the grain of the bone may cause it to split differently than intended. You can always adapt your plans to suit so as not to waste your time and materials.

- Let the shape of the bone blank help you decide on the final shape of the needle. Decide which end will be holed and which pointed. Pencil in the overall shape.

- Starting with a file or coarse sandpaper, begin refining the shape. Do not over-sharpen the point at this stage to avoid accidental breakage and finger-pokies. Remember to smooth down its broad sides as well as its profile. Take your time with this, pausing often to look at the overall shape.

- When you are satisfied with its general shape, but before spending too long on refinement and polishing, drill the hole. Start with the finest drill bit or awl or other boring tool and then widen its volume afterwards until the desired hole eye volume is reached. You may wish to have a scrap of the sort of yarn or thread you intend to use with this needle on hand, to check that it can be easily passed through the eye (camel-like). If the needle cracks at this stage, snap off the broken end and try again on your new, shorter needle. If it’s just not working, begin again with a broader blank and drill the hole before sanding the needle very fine.

- Once you are satisfied with the eye, continue refining the shape. Fine sandpaper, used wet, will reduce dust and produce a beautiful result. Sharpen the point last, as this needle will easily pass through sandpaper and your fingertip if you are not careful.

- For a mirror polish, finally rub all sides of the needle, dry, on a strop or other piece of polished leather, such as an old belt. It will only take a few passes for the lustre to really come out, if you have sanded it well by this stage.

Backwell, L; d’Errico, F; Wadley, L (2008). “Middle Stone Age bone tools from the Howiesons Poort layers, Sibudu Cave, South Africa”. Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (6): 1566–1580. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.006

-

‘All it needs is momentum’: Turning the wheel on handspinning

The girl in the polkadot coat peeked into the case. I observed her eyes roam over brittle rods, wooden discs, dusty clouds of wool. ‘Mummy, are they toys?‘ she sang, fogging the glass. Her mother, attention elsewhere, said she thought they might be before drifting onwards through the gallery.

Imagine a museum cabinet of the future, which houses the contents of your desk: coffee cup, pen, phone. Imagine your great-grandchildren passing this display, lost as to what the objects are, or how central they were to your day-to-day life.

At moments like this, the gulf between our lives and those of our recent ancestors is made apparent. The case, at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, contained timeworn spindles and whorls – tools of cloth production that would have shone in their heyday.

I enjoy myself every time I see spindle whorls in a museum. Today in the West we encounter few references to ‘spinning’, except perhaps in renditions of Sleeping Beauty or Rumpelstiltskin, though precisely what those ill-fated heroines were doing is quite lost on most people. When spinning is demonstrated, it reveals how jawdropping an achievement early textile production was; the typically brief explanation offered alongside museum display cases leaves us none the wiser.

The girl in polkadots therefore must be forgiven for calling them toys, especially as they share many characteristics with tops – playthings which practised the hand in preparation for a lifetime of spinning. Like a top, whorls can be as simple as a lump of clay or a disc of wood through which a rod – the spindle – is fixed. There are also beautiful whorls, in precious stone, glass, bronze, silver, and ceramic. Whorls occasionally speak to us out of the past. A Viking Age favourite of mine (see above), held by the National Museum of Iceland, has ‘I belong to Thora’ scratched into its surface. We know nothing of Thora, but that her spindle whorl was a proud personal possession, voicing its place in the household.

Archaeology has not yet been able to identify the origin of spinning as a human endeavour, though depictions of string garments exist from the Upper Paleolithic (20,000 years ago). Once thread was produced in the quality and quantity needed for weaving, some time in the late Neolithic, we can arguably state that humans entered the modern era.

It’s hard to overstate the centrality of spinning to human life and culture across the globe and across time. Considering that for the vast majority of traceable history, spinning was predominantly a female craft, we must view women’s history and spinning as firmly intertwined at the core of civilization.

Spinning continued as an essential home craft in the vast majority of cultures around the world, first with hand-spindles and then, from about 1030 in the Islamic world, using spinning wheels. Even after the Industrial Revolution transformed cloth production from the mid-18th century, handspinning continued across Asia, Africa, South America and in pockets of North America either as a subsistence craft or, in the famous case of cotton spinners in India, at the urging of Mahatma Ghandi in 1931, as a form of political action and cultural rebellion.

Around the same time, spinning could be seen in homesteads across my own country. Canadian Production Wheels, or ‘Quebec Wheels’, are now a highly sought-after antique. The Borduas family, the last traditional Quebec wheelmakers, who had produced as many as 52,000 wheels over the previous 80 years, closed shop in 1954 due to dropping demand. Yet their peak year had been 1920 – just 34 years earlier – when they shipped 1000 wheels to new owners. Despite the vast majority of cloth then being produced mechanically, handspinning remained an important rural craft well into my own parents’ lifetime. This isn’t the dim and distant past.

I was first taught to spin, as a homesick and underfunded graduate student, over tea and conversation by a lifelong enthusiast one rainy November night in Edinburgh, 2008. It spoke to something in my bones and since then I’ve produced hundreds of kilometres of yarn that has been worked into jumpers, scarves, blankets, socks, mittens, hats, and a dozen other things by myself, friends and family. It’s a thoroughly satisfying craft to undertake and to share with others. There’s nothing more soothing than the subtle weight and vibration of the spindle whorl at full speed, the precise tension control required to draft fibre from the batt, the quiet tap as the spindle meets the floor; or perhaps the gentle wooden purr of the wheel, responding to every subtle motion of the spinner. Handspun yarn feels alive, and precious, as the fibre has passed through the spinner’s hands as many as nine times before the yarn is finished. Thrifty as it ever was, spinning requires no electricity, and allows the mind and eyes to wander. It’s a social activity, and we know from depictions of spinners in art and literature, that women who spun together also found their voices together.

So, when I see those curious little discs in museums, all over the world, to me they’re more precious than the glittering treasures which draw the majority of visitors’ attention. If any objects were to be at the heart of our historical homes, most familiar to the hands of our female ancestors, it would be these.

People are coming back to spinning, and not just women. Anyone who wants to can learn to spin from craft groups in our local communities, or independently online. For many, spinning is a rejection of the unsustainable consumerism which has replaced traditional cultural expressions. There’s good demand keeping the few modern wheelmakers busy and a healthy trade in antique wheels. Spinners today are keeping their craft from entering the HCA’s red list for another year. Hopefully, by the time the girl in polkadots has a family of her own, it will be unremarkable for her to understand what she’s seeing in those dusty cabinets. All it needs is momentum.

Photo credits: All photos (2022) Nicole DeRushie

Further Reading

Barber, Elizabeth W., Women’s Work : The First 20,000 Years : Women, Cloth and Society in Early Times (New York: New York : Norton, 1994)

Black, Naomi and Gail Cuthbert Brandt, Feminist Politics on the Farm: Rural Catholic Women in Southern Quebec and Southwestern France (Montreal: Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014)

Brown, Theodore M. and Elizabeth Fee, ‘Spinning for India’s Independence’, American Journal of Public Health (1971); Am J Public Health, 98 (2008), 39

Craig, Béatrice, Judith Rygiel and Elizabeth Turcotte, ‘The Homespun Paradox: Market-Oriented Production of Cloth in Eastern Canada in the Nineteenth Century’, Agricultural History, 76 (2002), 28-57

—‘Survival Or Adaptation? Domestic Rural Textile Production in Eastern Canada in the Later Nineteenth Century’, Agricultural History Review, 49 (2001), 140-171

Crowley, T., ‘Experience and Representation: Southern Ontario Farm Women and Agricultural Change, 1870-1914’, Agricultural History, 73 (1999), 238-251

Foty, Caroline, Fabricants De Rouets: Nineteenth Century Quebec Spinning Wheel Makers and Their Twentieth Century Heirs (1850-1950) A Provisional Directory, 3rd ed. (Online publication, 2018)

Hood, Adrienne D., ‘The Material World of Cloth: Production and use in Eighteenth-Century Rural Pennsylvania’, The William and Mary Quarterly, 53 (1996), 43-66

Inwood, Kris and Phyllis Wagg, ‘The Survival of Handloom Weaving in Rural Canada Circa 1870’, The Journal of Economic History; J.Eco.History, 53 (1993), 346-358

Lewis, Robert, ‘The Workplace and Economic Crisis: Canadian Textile Firms, 1929–1935’, Enterprise & Society; Enterp.Soc, 10 (2009), 498-528

Milliken, Emma, ‘Choosing between Corsets and Freedom: Native, Mixed-Blood, and White Wives of Laborers at Fort Nisqually, 1833-1860’, Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 96 (2005), 95-101

Muldrew, Craig, ”Th’Ancient Distaff’ and ‘Whirling Spindle’: Measuring the Contribution of Spinning to Household Earnings and the National Economy in England, 1550-1770′, The Economic History Review, 65 (2012), 498-526

Ommer, Rosemary E. and Nancy J. Turner, ‘Informal Rural Economies in History’, Labour (Halifax), 53 (2004), 127-157

Pacey, Arnold, Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 1991)

-

Environmental Connectedness and Wellbeing

It is increasingly common to find articles in mainstream media touting the health benefits of time spent in nature (in one aspect, referred to as ‘wilderness therapy’ or WT), often with a cultural shading which encourages us either to explore the mentality of our ancestors, or that of another culture perceived to be holistic and enlightened in its approach to wellness.

Friluftsliv (a term coined by the Norwegian, Henrik Ibsen in 1859) is a concept which is generally accepted as a basis for wellness activity and educational reform in Scandinavia and beyond, including the emergence of Forest School in the United Kingdom in the first decade of the 21st century.

The benefits of WT are coming to be well-recognised, and cross-cultural, cross-national studies are beginning to show the universal applicability of core therapy concepts (Harper et al, 2018). Friluftsliv may be a named cultural concept in Scandinavia, however as several researchers have established, the concept is not exclusive to Scandinavian culture and therefore is a useful way of naming the positive connection between individuals and the natural environment on a much broader scale.

Most recently, a study by the Norwegian Pål Lagestad and academic partners, which appears in the Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership (2019) touches on the importance of friluftsliv to wellbeing and indicates the benefits of tracking participation in traditional friluftsliv activities as an indicator of general youth activity levels as well as the health of social relationships both within and beyond the cultural confines of Scandinavia.

Although the translation and definition of friluftsliv varies (see Beery, p.93 for a sampling of definitions which have appeared over the last twenty years), at its core is the concept of wellness achieved through time spent in the natural environment. It has been well-established through research that the cultural concept of friluftsliv is related to the psychological concept of Environmental Connectedess (EC), and in Scandinavia is recognised in and by every age group which has come under direct study (ibid).

Such studies suggest significant implications and recommendations for access to nature, outdoor recreation and education (see also Mikaels, 2018). Pilot studies have indicated substantial positive mental health benefits to time spent in nature (Mutz and Müller, 2016).

Conversely, inactivity among youth and their perception of family relationships has been found to have a direct connection, in Lagestad’s study, to their level of participation (or lack thereof) in traditional friluftsliv activities, where inactivity in these areas can be used as a predictor of general inactivity. (p.21)

Lagestad’s study stands on the shoulders of, and reflects the general findings of WT research, best summarised by Odden (2008), that ‘Traditional outdoor recreational life may constitute an important positive contributor to children’s physical and mental health’ and that ‘Friluftsliv activities may have a major and lifelong effect on health and quality of life.’

The rationale for the study by Lagestad and his colleagues is that ‘increased knowledge of factors that predict inactivity is critical for preventing people globally from becoming inactive in friluftsliv. This knowledge may find applications with governments, teachers, and family members, who are all attempting to establish habits of engaging in friluftsliv in young people.’ (p.22)

In establishing the power that natural environments have over urban environments, the article quotes F. Nansen (1922), establishing as traditional and long-held the concept that the benefit of immersion in the natural environment is not solely a result of improved physical fitness: ‘The first great thing is to find yourself, and for that you need solitude and contemplation. I tell you deliverance will not come from the rushing, noisy centres of civilization. It will come from lonely places! The great reformers in history have come from the wilderness.’ (p.22)

Lagestad’s study (among others) confirms through research the contemplative power of friluftsliv, with 90% of participants reporting a desire to experience silence, tranquillity and ‘fresh air’ as driving their choice to engage with the outdoors, and that many traditional activities require no specialist equipment, skill or knowledge, thus making these wellness factors readily available to all. (p.23)

Such concepts come as no surprise to anyone who has experienced the sense of replenishment and cleansing that comes with time spent in woodlands. Even as a small child, I recall the special feeling that was to be had during long canoe expeditions into the Northern Ontario wilderness – tens of thousands of square kilometres of forests, lakes, rivers and wetlands, and glimpses of the majestic Canadian Shield granite over which we travelled – being sometimes many days travel on foot and by paddle from the nearest road or access point, bringing with us all we needed and relying on natural fresh water sources and firewood gleaned from the forest while in camp.

The silence in the evening was so profound, we felt deafened by a strange buzzing in our ears coming from everywhere and nowhere – the sound, as my mother explains it, ‘of life.’ These were opportunities for our parents to pass on traditional skills – fishing, paddling, map reading and navigation, identifying species, tying knots, first aid, safe handling of fire – everything needed for survival in a total wilderness.

I can recall from early on a sense of connection with history and tradition, that these were skills needed by my ancestors and those of the people who are indigenous to the land, and that the place held spiritual significance. I recall soaking my skin and hair in the lakes just before leaving, allowing it to dry and feeling reluctant to ‘wash the woods off’ once home. I always carried, and still do, a fragment of wood or a stone, taken as a talisman to keep the woods with me and feel the continued psychological benefit of environmental connectedness.

In the Carolinian forest at home, just a few hundred miles further south, towering hardwoods create, again in the words of my mother, ‘our cathedral’. What do we do there? Simply be: observe nature, experience it with our senses, walk, sit, think, pick berries, tell stories.

Not a religious woman in the traditional sense, my mother’s phrasing hints at what time spent in woodlands offers a person: a feeling of connecting with something much larger, leading to a sense of personal replenishment and wellbeing.

In times of personal struggle, with mental and physical health, it was only really by retreating into the wilderness that I felt any real progress towards a rebalance. In times of stress, I daydream of being ‘out there’. If that’s not possible, I watch my favourite vloggers on YouTube who record their wilderness camps and bushcrafting activities, and the sights and sounds of the wilderness they share with viewers is profoundly soothing – the ultimate ‘slow TV’, to reference a related Scandinavian wellness phenomenon.

It is also at times of wilderness immersion when I feel a strong connection to my family, especially those I share the experience with, and thankfulness for the skills and knowledge that have been passed on to me through teaching and example. These experiences are anecdotal evidence only, but compelling, of the validity of Lagestad’s findings, and especially so as these experiences were and are obtained outside of the cultural home of friluftsliv, yet touch on the same core ideas.

However, the research of Lagestad and others has established that a decline in participation in friluftsliv activities (60% in 1997, and 40% in 2014) in the general population is attributable to a particular decline in participation among young people. Moreover, young people today tend to be drawn toward friluftsliv activities which are perceived as ‘exciting’ (such as skiing, climbing) but which are simultaneously exclusionary, involving expense, technical skill, equipment and travel which not only prevents many from being able to engage in them, but which for those that do, can stand in the way of a meaningful engagement with the outdoor environments in which such activities are carried out.

Moreover, preference for such sports means many traditional activities are not receiving attention and are being lost. (p.23) Additionally, the study is based on sociological theory, specifically regarding the role of family and friends in shaping a person’s cognitions and behaviours.

People are more likely to engage in friluftsliv if this is an activity shared by their social network. People who are most likely to engage lifelong in healthy levels of activity are those who have had a strong influenc upon them as children to engage in activity, with parents having the strongest positive or negative influence. (p.29)

When establishing the connection nurtured by Forest School between participants and the woodland, it is important to consider the points above, that not only is it an opportunity for the environment itself to create positive feedback in the client, with noticeable improvements in mental and physical wellbeing associated with opportunity to spend time regularly and often outdoors, it also fills the gap in socialising clients toward a nature-based wellness model if such socialisation is not otherwise present in the client’s life.

I was lucky to have the example and motivation of parents who understand the benefits of living an outdoor life, but know from the anecdotes of my contemporaries that many have not shared this experience, and for them, the outdoors was and is an unknown, uncomfortable environment.

Sara Knight puts it well in her conclusion of Forest School for All, where she directly addresses the influence of friluftsliv on the Forest School guiding principles: ‘Habits of quiet contact established at a young age can offer balm and healing when we encounter the normal bumps and bruises of life.’ (p.240) Forest School provides the chance to create a ‘woodland family’, where Leaders and other participants provide a positive example for clients and so establish positive patterns of thought and behaviour, as a parent might with a child.

Additionally, Leaders are able to pass on traditional knowledge and skills, so that these – crucial as they are to a continuation of accessible, culturally significant friluftsliv activities, no matter the national or cultural setting in which they are undertaken – may see a resurgence, or at least a slowing in their decline.

Such an opportunity as Forest School provides will be of personal significance to all participants, for cultural sharing and connection with the natural environment, helping participants towards wellness in its many aspects.

Beery, Thomas H. Environmental Education Research. Nordic in nature: friluftsliv and environmental connectedness. 2013, 19:1, pp. 94-117.

Harper, Nevin J., Leiv E. Gabrielsen and Cathryn Carpenter Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning. A cross-cultural exploration of ‘wild’ in wilderness therapy: Canada, Norway and Australia. 2018, 18:2, pp. 148-164.

LaBier, Douglas. Why Connecting With Nature Elevates Your Mental Health. Psychology Today. 2018, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-new-resilience/201801/why-connecting-nature-elevates-your-mental-health

Lagestad, Pål, Tina Bjølstad and Eivind Sæther. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership. Predictors of Inactivity Among Youth in Six Traditional Recreational Friluftsliv Activities. 2019, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 21–36.

MacEachren, Z. (2013). “The Canadian Forest School movement.” Learning Landscapes, 17(1), 219-. Available at: http://www.learninglandscapes.ca/images/documents/ll-no13/maseachren.pdf

Mikaels, Jonas. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership. Becoming a Place-Responsive Practitioner: Exploration of an Alternative Conception of Friluftsliv in the Swedish Physical Education and Health Curriculum. 2018. Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 3-19.

Mutz, Michael and Johannes Müller. Journal of Adolescence. Mental Health Benefits of Outdoor Adventures: Results from Two Pilot Studies. 2016. Vol. 49, pp. 105-114.

Odden, A. What is happening with Norwegian outdoor life? A study of trends in Norwegian outdoor life 1970–2004 (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2008.

Ritchie, Stephen, Mary Jo Wabano, Rita G. Corbiere, Brenda M. Restoule, Keith C. Russell & Nancy L. Young. Connecting to the Good Life Through Outdoor Adventure Leadership Experiences Designed for Indigenous Youth. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning. 2015, 15:4, 350-370.

Grounded History

BAH & MA in Medieval Studies, L3 Forest School Leader, PGDE. Traditional knowledge and skills. Spinning, mostly. Public History MA 2022 Royal Holloway University of London