I’ll do my best to write about fig pudding without mentioning Christmas.

Whoops.

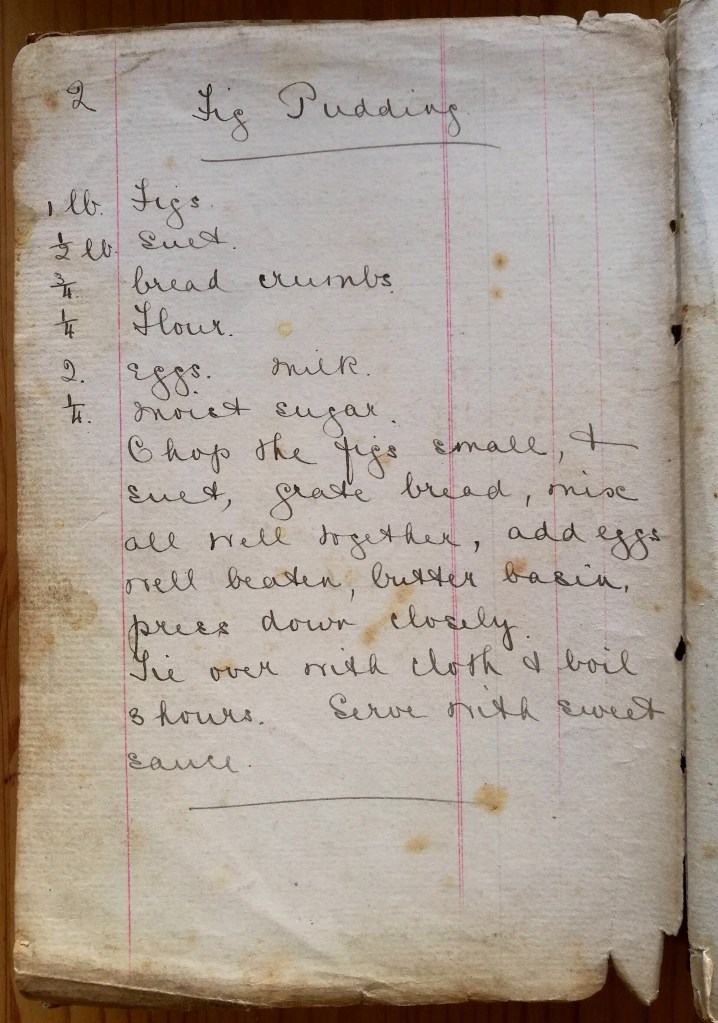

In truth, this recipe doesn’t much resemble a holiday classic: no fruit other than the figs, no spice and no alcohol. The recipe given as number two in the collection has much more in common with very old recipes for fig pudding, which tend to be simpler in terms of ingredients and instruction. One of the earliest boiled ‘fygey’ pudding recipes comes from that famous 14th century cookery book, The Forme of Cury. Dried figs, being lightweight and fairly bombproof, were widely available in Britain in the medieval period, which explains why they, as with dates and raisins, appear again and again in ancient recipes as well as their modern equivalents in the canon of ‘Traditional’ British sweet dishes. They were exotic and luxurious while also being accessible, price wise, for most. The medieval recipe by today’s standards ticks many dietary boxes: vegan-ish and gluten-free, but characteristically lacks most of what we would expect in the way of instruction.

FYGEY. XX.IIII. IX.

Take Almaundes blanched, grynde hem and drawe hem up with water and wyne: quarter fygur hole raisouns. cast þerto powdour gyngur and hony clarified. seeþ it wel & salt it, and serue forth. —The Forme of Cury recipe 118

Take blanched (peeled by boiling) almonds, grind them and mix with water and wine, quartered figs, whole raisins. Add to this powdered ginger and clarified honey. Boil it well and salt it, and serve it up.

This sweet dish isn’t to be confused with ‘Fygey’ from later in the same volume: a fish and onion stew. Isn’t English wonderful?

Even this very early recipe, which bears more than a passing resemblance to dishes that would have been familiar in the ancient Classical world, calls for spice and wine, which our late Victorian recipe does not.

These omissions make me think that the recipe included in this book, like the previous one, Pudding a la Rachel, was viewed as simple, everyday fare as opposed to the kind of ‘speckled cannon-ball…blazing in half a quartern of ignited brandy’ that would have been special enough to flush Mrs Cratchits’ cheeks.

This recipe comes with one or two mysteries. The milk, for example, in a slightly more thready pen stroke, comes without measurement attached, but next to ‘eggs’. This makes me think that the liquid volume of 2 eggs, on trying the recipe, left the mixture too dry, so milk was added until the right consistency was achieved. This accounts for no measurements – the point is to remind the maker that milk may or may not be needed, and it should be used by gut feeling. The second mystery is the mention of ‘moist sugar’ – which could be white sugar which does not come in hard, dry lumps, or it may refer to brown sugar. I have used brown sugar in making mine, as it would lend some very welcome warmth of flavour to the finished product.

It’s a reminder that for many, practice and experience gave cooks a ‘feel’ for things, and that cooking was an instinctual art, rather than a science. Anyone who has spent any time reading old cookbooks will know how minimal, how barely suggestive, many recipes are. A recipe for chicken pie might be rendered as briefly as ‘Make a pie. Fill it with chicken and serve with sauce.’

While recipe one made this collection feel as if it was in conversation with recent food fashions, this recipe is full of echoes from the distant past.

Fig Pudding

1 lb (454g) figs

½ lb (227g) suet

¾ lb (340g) bread crumbs

¼ lb (113g) flour

2 eggs (milk)

¼ lb (113g) moist sugar

Chop the figs small, & suet, grate bread, mix all well together, add eggs well beaten, butter basin, press down closely. Tie over with cloth & boil 3 hours. Serve with sweet sauce.

A quarter recipe, for convenience

113g figs (7 approx.)

57g suet

85g bread crumbs

28g flour

1 egg (milk)

28g moist (brown) sugar

Follow the simple instructions above. I used one whole egg and no milk and achieved a perfect ‘press-able’ consistency. The moistness of your breadcrumbs may yield different results, so use your judgement. I buttered a small pudding basin, pressed in the raw pudding, covered it with buttered baking paper then used a circle of damp 100% white cotton (from an old bedsheet) and a piece of cotton string over the lip of the bowl. Into a saucepan I put the basin, covered with a saucer, added boiling water about halfway up the sides of the basin, and lidded the pot. Brought it to a simmer and steamed the pudding for 1 hour.

Cook’s notes

This pudding doesn’t ‘sing’ in the copper as Mrs Cratchit’s did. Instead, it tap-dances. What’s helpful about it is that you can hear if the water is getting low without having to peek.

Provided you enjoy very simple flavours, this pudding is a homely, comforting treat (I have had mine with a good dollop of hot custard). The toasted breadcrumbs provide just as much flavour as the figs and the brown sugar, so it’s definitely bread-pudding in profile. Served warm, the pudding is dense and chewy, not overly moist. I might have needed to add milk after all, or possibly reduce the cooking time. In any case, it’s perfectly edible.

Does it want more flavour? I’d be tempted to add a pinch of salt, possibly some nutmeg, and no doubt our original recipe writer would have felt free to as well. A recipe is just a suggestion, after all.

Sounds great. I wonder if they might have used fresh figs? The trees grow well in a protected spot in this climate. Where I grew up in Sheffield they grew alongside the warm water of the canals and rivers close to the outlets for cooling water from factories and power stations, or so I remember reading in Flora Brittanica.

LikeLike

I think it’s entirely plausible that where fresh figs grew, they might have been eaten. You get a good micro-climate inside walled gardens that also made such things possible. Dried fruit was also a major import, so no matter what, figs could be had.

LikeLike